Memories of the Nineties

2018:März //

Coming from the English Westcountry, the sea, rocks, trees and flowers, and moving to the Regency town, with ice cream facades and eruptive weekend regional violence, and listening to music from the 60s and 70s although born in 1972, I didn’t have a clear sense of the cultural historical time I was living in. I experienced a kind of ‘slippage of time’. Nature and experience was filtered through and reflected off pop culture.

With eyes on America and Europe, I was under the spell of eras through a particularly Western focus. A positive nostalgia for unlived and imagined times. Rather than a dominant style or movement there was a plurality of forms and historical ‘expressions’. The past exerted a strong influence, a strong gravitational pull. There was however a sense of direction and optimism. The world was big. The horizon distant. There was a ‘beyond’. A ‘real’ to be discovered outside of signs and language. A portion of innocence. For navigation, a copy of Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer … or was it Capricorn in my back pocket, and a head full of Abstract Expressionism and Black Sabbath.

The Edifice

Mid 90s and the Cheltenham art school painting department was still enthralled by Modernism and it’s histrionics. In the library one experienced a divergance between how one felt (selfconscious, half intoxicated by images), the media saturated pop present, and the reproductions of the 20th Century masters and legends one was referred to and thrilled by. Unconsciously placing oneself in relation to a heroic past and carrying the baggage.

Western Art History felt like an edifice. A huge block of genius. An elevated road of charisma that had reached a vanishing point. A horizon lined with the silhouettes of gods. “We are untouchable!” they smiled from amber tombs. Cracks in the pantheon were then searched for.

Critcal discourse, post structuralism and feminist theory questioned the unifying dominant culture, it’s organising principles, power relations and hierachies. Even partly digested these theories offered ways to develop new approaches to culture and received, authorised history. At the same time there was a kind of euphoric wind blowing from London, a slick stream of one liners from a younger generation of artists who were being celebrated in the present and achieving success. This signified the development of a new kind of fast, professional, young British art scene.

It was beginning to feel like a party at the end of time, the end of chronological, linear time. The surface of the path started to ripple, take off, images blowing around tethered to the weakening gravity of history and meaning. Cracks becoming lines of potential. Signs proliferating.

Death of a Painting. Hole in the Wall.

I recall the painting that died in my arms. It was a version I was making of Velázquez’s The Flagellation of Christ. Historical ochres and umbers splashed on an endless field of bright pink. An open ended heavy pop laceration … But wait! At that time I was still excited by painting! Anyway, at some point I was standing in front of a canvas going through the motions (painting at that time felt like an elevated theatre stage, or cinema screen on which one performed roles and reenactments) when my belief in this construct left me. With all the passion I was feeling I might as well have been painting a brick wall. I was more interested in everything around me, objects, wall, floor, body, ‘happenstance’. Perhaps it was the empty space, the aura, the afterglow of the deceased painting that gave these things their vivid presence.

I decided to make a hole in the wall.

The Body

‘The corporeal’ appeared to be the locus of ‘the real’, a ‘natural’ physical reality and experience. The opening up of which could reveal potential, disturbing truths, countering the abundance and authority of circulating signs, surfaces and simulacra. ‘The body’ was put into multiple discourses in relation to notions of ‘the self’ and identity. As a property, as a political site inscribed by systems of value and invested by language. The interrelation and instabilty of these terms were at the same time questioned. The body and abjection. Julia Kristeva’s concept of the Abject. That which is cast out, which provokes subjective horror through a disturbance of integrated identity, a disruption of the categories of subject and object.

In this context I became interested in how paint, substances, drips and stains could implicate the body and its ‘base’ materials, fluids, forms, functions and limits. Knotted bedsheets for guts. How this relation could de-sublimate the elevated art object, it’s associations and meanings, revealing the hidden, unconscious drives lurking within. The mark, the blob relating to the amorphous, the formless. A liminal state. The accidental splash, the trace of an event, a pressurised spurt that leaves the body rupturing it’s unity. The loss of self and the out of control. The fragmented, disorgnised body. Jolly horrors!

Entries and Exits

Mid 90s. Whilst in the middle of building an installation I was turned onto the concept of rhizome from A Thousand Plateaus, by Deleuze and Guattari, which became a toolbox of sorts. Freed from the confines of canvas, the work erupted in the actual given space. ‘Live’, improvised, temporary, incorporating and employing materials that came to hand, e.g. a blanket, stool, slapstick banana skin, underwear, a shoe, and other associational materials that implicated the body, physicality, and psychosexuality. Through extending, tearing and ripping into the surfaces, revealing layers, the limits of space and work blurred. Non hierachical growth in all directions at once, high and low, inside out. A deterritorialization, relating to the thresholds of identity, of psychological and physical space. Leakage, spillage over a border. Dissolution. A process not a product. A simultaneous collapse and growth. A becoming.

Desiring to cut through surfaces, the fabric of space, looking for ‘the real’, only other surfaces and endless layers appeared, one mask removed to reveal yet another … In the 1990s the Twentieth Century started to look back on itself, to gaze into a mirror and identify with it’s reflection, cannibalising and devouring itself. In the process forgetting it’s reality, it’s presence, and becoming image, becoming the reflection in the looking glass.

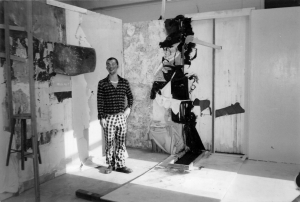

Ben Cottrell, untitled, 1996,

Degree show, Cheltenham School of Art, England